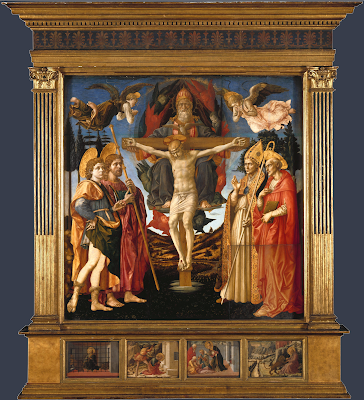

Inspired by the recent exhibition at the National Gallery, by eye is activated by the panels of Pesellino. Commissioned in 1455 by a confraternity, the artist combines tradition and innovation, paving the way for better-known artists to come. The work has had an exceptionally complicated life. Sawn up in the eighteenth century, the panels have slowly made their way to the National Gallery to be put back together, with the first panel (the Trinity section) acquired in 1863. One panel remains missing, restored here in the bottom right corner, prompting debates surrounding the rights to restoration. Putting the work back together certainly would have been a jigsaw puzzle, reflecting the challenge of piecing together the life of Pesellino, an understudied artist of the Italian Renaissance.

There is a Botticellian aesthetic running throughout the piece, and Pesellino prefigures the Florentine master in many ways. The flying angels at the top of the panel bear a direct relation to Botticelli's Mystic Nativity, produced nearly half a century after Pesellino began this commission. Even the colouration recalls Botticelli's floating angels, as they occupy the same point highest in the picture plane, floating in a flattened space. But arguably Pesellino even achieves a greater sense of foreshortening in his earlier piece, especially the feet of the left-hand angel which really push into the viewer's world, conflating reality and divine. As a devotional piece, this would have been especially sensory for the contemporary onlooker. The ombre skies in Pesellino's work, from a deeper blue to lighter at the base of the cross, form an intriguing take on atmospheric perspective in such a compressed space, echoed in Botticelli's Mystic Nativity. Pesellino was being extremely innovative. Admittedly in some areas it is more difficult to ascertain each hand of the artist. In the dark ground that they stand on, and the highlighting placement of the base of the cross, this seems to be Lippi's work (recalling his Adoration in the Forest from a similar date). But in the individuality of faces, one would assume the hand of the original artist. The features of Saint Jerome on the far right, for instance, can be directly connected to Pesellino's Madonna and Child with Saints now at the MET, attributed to a slightly earlier date.

Pesellino proves he is a master and worthy of art historical re-examination. He can do large scale commissions such as this altarpiece, with documents stating it cost 150-200 florins, a huge amount in the fifteenth century. He can hark back to the early Renaissance; flat compositions with an exquisite gold background as the work at the MET illustrates. He can introduce and pioneer new forms, from a multifigural, proportional composition to attempts at a recessional background with a naturalistic landscape. He was a meticulous planner, as preparatory drawings for this altarpiece at the Uffizi testify. But he could also work on a small scale. Not only do the detailed predella panels on this altarpiece highlight this in their rich rendering of the lives of saints, but Pesellino gained fame through his cassone chests. He could therefore operate in the private and public realms, bringing objects to life in religious spaces but also in domestic environments. This is why he gained contemporary fame, enough to receive prominent commissions such as this. But fundamentally he can do all of this whilst maintaining religiosity, with devotion remaining at the heart of artistic style, form and narrative.

Comments

Post a Comment